A couple of days before Christmas, I went to see the NHL’s Nashville Predators play on their home ice against the defending Stanley Cup champion Colorado Avalanche.

Amid all the silliness of a modern pro sports experience – the home team skating out of a giant saber-toothed tiger head, the mistletoe kiss cam, a small rock band playing seasonal hits between periods – there was a steady stream of advertising for DraftKings, a company known as a sportsbook that takes bets on athletic events and pays out winnings.

Its name flashed prominently on the Jumbotron above center ice as starting lineups were announced. Its logo appeared again when crews scurried out to clean the ice during timeouts. Not only was “DraftKings Sportsbook” on the yellow jackets worn by the people shoveling up the ice shavings, it was also on the carts they used to collect the ice.

This all came a few days after the Predators announced a multiyear partnership with another sportsbook, BetMGM, that will include not only signage at their home venue, Bridgestone Arena, but also a BetMGM restaurant and bar.

If I had cared to that evening, I could have gone onto the sports betting app on my smartphone and placed a wager on the game. Tennessee is one of 33 states plus the District of Columbia where sports betting is legal. On Jan. 31, 2023, Massachusetts became the latest state to legalize the practice.

The point of depicting the whole scene is simply this: In the nearly five years since the Supreme Court allowed states to legalize sports betting, a whole industry has sprouted up that, for tens of millions of fans around the country, is now just part of the show.

Betting’s seamless integration into American sports – impossible to ignore even among fans who aren’t wagering – represents a remarkable shift for an activity that was banned in much of the country only a few years ago.

A new sports world

Let’s look at the numbers for a start.

Since May 2018, when the U.S. Supreme Court overturned a law that limited sports betting to four states including Nevada, US$180.2 billion has been legally wagered on sports, according to the American Gaming Association’s research arm. That has generated $13.7 billion in revenue for the sportsbooks, according to figures provided to me by the AGA, the industry’s research and lobby group.

Before the NFL kicked off last September, the AGA reported that 18% of American adults – more than 46 million people – planned to make a bet this season. Most of that was likely to be bet through legal channels, as opposed to so-called corner bookies, or illegal operatives.

So, who’s betting on sports? In an interview, David Forman, the AGA’s vice president for research, told me that compared with traditional gamblers – those who might play slots, for instance – “sports bettors are a different demographic. They’re younger, they’re more male, they’re also higher income.”

They’re people like Christian Santosuosso, a 26-year-old creative marketing professional living in Brooklyn, New York. Santosuosso didn’t bet on games until it became legal. Now he and his buddies will pool their money on an NFL Sunday to spice up both the interest in a game and the conversation in the room.

“It’s entertainment,” he told me in a phone interview. He explained that even a tough gambling loss can be amusing or funny, a way to look back on the mistakes your team made that ended up affecting whether you won the bet. But he added that he has a limit on how much he’ll bet.

Coverage and conversation

Shortly after Supreme Court ruling in 2018, I wrote a piece for The Conversation asking if the media would start to produce content aimed at bettors.

The answer has been an unequivocal “yes” – and it seems to have helped change the way sports betting is talked about.

As I write this, if I look at the front page of ESPN.com, I see that the University of Georgia is a 13.5-point favorite over Texas Christian University in the college football national championship. It’s front and center, right next to the kickoff time and the TV network where it’s airing.

But that’s the least of it.

ESPN has broadcast a gaming show since 2019, “Daily Wager.” In September 2022, the sports conglomerate announced an array of new content centered on betting advice and picks. And SportsCenter anchor Scott Van Pelt is famous for his “Bad Beats” segment, in which Van Pelt typically highlights how a team on the winning side of the point spread falls apart at the last second in a crazy way.

Meanwhile, a cottage industry of betting tip channels has emerged on YouTube – if you type “#sportsbetting” into YouTube’s search bar, you’ll find thousands of them.

Another example of how things have changed: On Jan. 2, 2023, the University of Utah’s football team had the ball first and goal with 43 seconds left, down 21 points to Penn State in the Rose Bowl. The game was essentially over. However, the commentators noted that a touchdown would mean a lot to some people.

Who? Why? The announcers didn’t elaborate, but the implication was obvious: Those who had bet the over – wagering that together the two teams would score more than 54 points – had a lot riding on that touchdown. So, in a sense, did ESPN. In a blowout, fans of both teams are likely to tune out. But when there’s money riding on something like the over, eyes stay glued to the screen.

Utah ended up scoring on third down with 25 seconds remaining. Final score: Penn State 35, Utah 21.

The danger and the ceiling

I’ve been editing sports articles since the early 1990s and have run the sports journalism program at Penn State since 2013. I have noticed how my students now routinely talk about the point spread – the expected margin of victory – and even the over-under, a wager on the total number of points scored.

That just did not happen so often when I first got to State College, nor in the newsroom before that.

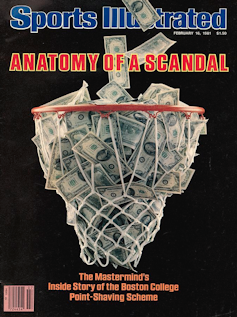

Sports Illustrated

Sports leagues were once vehemently opposed to gambling. And while they’re still concerned about keeping players from betting, many leagues – particularly the NFL – have made a complete U-turn since legalization.

There are multiple reasons for this change of heart. While the concern used to be about losing the integrity of the game to a betting scandal, now sports leagues can argue that legal betting allows for better monitoring of potential cheating. If heavy betting happens on one team, or if there’s sudden shift in betting patterns, it’s all visible to the sportsbooks and might indicate nefarious activity.

There’s also significant fan interest in legal wagering – 56% of Americans adults, and nearly 7 in 10 men, recently told Pew that they’ve read at least a little about how widespread legal sports betting has become.

And, of course, there is big money from a new sponsorship group – the sportsbooks – that helped drive overall NFL sponsorship revenue to a record $1.8 billion in the 2021 season.

The danger, of course, is gambling addiction.

And while the AGA is quick to note that its member companies pledge to give information about problem gambling to their customers, legalization has undoubtedly provided easier and more secure access to sports betting.

Keith Whyte, executive director of the National Council on Problem Gambling, said in a telephone interview that research by his group had found that roughly 25% of American adults bet on sports, somewhat more than the AGA’s estimate. That percentage has jumped from roughly 15% before the Supreme Court ruling, per the NCPG.

While that’s a big increase, it also suggests that perhaps there is a ceiling coming up – in other words, when all the states that will do so legalize sports betting, wagering still won’t be done by many more people than now, Whyte speculated.

“I think it’s changing the market in a lot of ways,” Whyte said, “but my guess is it’s mainly to increase the intensity – and associated risk of problem gambling – among fans that were already engaged fans.”![]()

John Affleck, Knight Chair in Sports Journalism and Society, Penn State

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.